The establishment of fascism in Germany in January 1933 was a result of the political victory of the dysfunctional groups of big and small businesses over the financially sound parts of the German economy. We have been at pains to show how the near entirety of German finance capital had coalesced by the end of 1932 on a policy bent on violent expansion and war. With the setting up of the Hitler Government on January 30 Germany entered the path of an economic policy of disequilibrium and capitalist dysfunctionalism.

This might appear to be an absurd proposition. However, looking at world capitalism caught in the general slump of the 1930’s one is driven to the conclusion that this crisis was the first in the history of capitalism which did not end in the restoration of economic equilibrium serving as a basis for renewed prosperity. In this instance, the capitalist system was lifted off the rock of stagnation only by means of the arms race forced upon the world powers through the initiative of German fascism preparing for world war. There was, admittedly, a vestige of business revival in England in 1932 and in the U.S.A. in 1933, neither geared to war preparation. But by 1937 Roosevelt’s New Deal had spent its pump priming and reviving force and the American economy was on the verge of relapsing into renewed stagnation. Similar developments of rising unemployment followed in Great Britain. In essence, the sequence to the world slump consisted of ten years of war economy.

Hence it is no figment of the imagination to classify the kind of capitalist economy which was created in Germany in 1933 as a viable system of dysfunctional capitalism. This paradoxical formula can quite well serve as a definition of the fascist system of economy. What German finance capital needed above all was to break out of the falling rate of profit by the only means in existence that did not depend on other capitalist powers nor on the world market, a forced raising of the rate of surplus value by the slashing of the workers’ wages. Throughout the slump and its consequent unemployment, which in 1931 reached three to four million in Germany and almost doubled in the following year, the employers and the Government had enforced drastic wage cuts. The trade union leadership hardly offered any resistance because of the hopeless weakness of workers striking under such conditions, and the workers themselves, under these conditions, accepted the necessity of a measure of wage cuts. But the same repressive policy was pursued even from the autumn of 1932 when the economic pressures of the slump were beginning to ease and a hope of revival of business activity was apparent. In September the Papen Government adopted a programme of public job creation to speed up the reduction of unemployment. The employers and the Government still insisted on further wage cuts. But now the workers were no longer in the mood to accept such measures. The result was an aggravation of the class struggle throughout Germany.

A growing militancy of the workers spread throughout the major industrial centres. At the beginning of November a spectacular strike broke out in Berlin involving over 20,000 transport workers. It was communist led and was opposed by the social-democrats and the trade union bureaucracy. It coincided with the Reichstag election of November 6, a fact which induced the Nazis under Goebbels to join the strikers. Goebbels declared later on: ‘If we had withdrawn from the strike, our footing among the working men would have been shaken.’ When the election was over the strike was soon defeated, but it had assumed a vital political character and aroused sympathy and excitement throughout Germany. The passive attitude of the workers was drawing to an end. Moreover, the election had produced the first major defeat for the Nazis who had lost two million votes, whilst the communists gained seven hundred thousand. For the big industrialists and the government this involvement of the Nazis in the working-class fight and their shattering electoral defeat raised the frightening prospect of the Nazi Party losing its grip on the masses and served as a warning of the urgency for action. If the fascist party were really to disintegrate, which way would the masses move? For the ruling circles scheming for the final dictatorship time was running short. Their economic plans, almost completed by then, were in jeopardy.

The strength of the working class was paralysed by the split between communists and social-democrats; the more the communists improved their fighting strength, the more the social-democrats thought fit to lie low. They urgently wanted the collapse of the Nazi Party but seemed to believe that their inaction would result in its disintegration. Meanwhile their immediate fight was directed against the communists rather than the Nazis, while the communists attacked the social-democrats as ‘social fascists’.

But when, in January, the formation of the Hitler government had saved the Nazis, the industrialists saw their hopes mature in the expectation that their obedient tool would break the organised working class. The Nazis indeed were not slow in doing just that, but in such a way that they wrenched themselves free from the shackles by which the bourgeois politicians had thought to constrain them. By calling for new Reichstag elections and making the most of the electoral campaign, setting the Reichstag on fire to unleash the terror on the communists, by creating the concentration camps and making ‘Gleichschaltung’ (compulsory conformism) their main strategic weapon for subduing all other political forces while playing havoc with the rule of law, they enforced their supremacy over their bourgeois partners in power. This, incidentally, adds to the explanation as to why Hugenberg’s position became untenable in the original Hitler cabinet which in March had been augmented by Goebbels.

However, the Nazis having won so much rope for themselves continued with greater momentum to follow the agreed programme for saving capitalism. On May 2, after celebrating May Day with colossal pomp and glory, they crowned the destruction of the working class parties with the dissolution of the Free Trade Union Movement by occupying their central building in Berlin and throwing numerous union leaders into concentration camps. Next, a government decision was taken to speed up the reduction of the enormous unemployment figures by making the employers add a number of unemployed to their existing work-force. These additional workers were paid hardly more than their previous unemployment allowance, but in order to switch the payment of it on to the employers the regular workers were deducted a percentage of their wages. In this way the overall pay-load of wage-labour was brought down to an extreme low level. Even Hitler himself thought fit to avow in a public speech that such wages were unworthy of a nation of an elevated cultural standard like the Germans, but that the speedy liquidation of unemployment, which he assured was the concern he had foremost at heart, was best served by this method of a ‘quantity-prosperity’ (Mengenkonjunktur), as he called it, where the workers were not benefited by higher earnings but their families were helped by a higher number of contributors to their budget.

This wages policy performed a big step in the direction of a fascist economic system but it did not achieve its structural completion. Throughout the first year of its existence the Hitler-regime made up its slow industrial recovery mainly on the basis of civilian production subsidised by various job creation schemes. Rearmament, its vital objective, commenced at the beginning of 1934. This brought about a clear-cut bisection of the German economy: one part occupied with the provision of the necessary reproductive values for the upkeep of the population, that is, the production and marketing of food, clothing, housing, etc. and their means of production; the other part devoted to munitions, arms, military building like fortifications and above all the erection of the military reserve-capacities (in England termed ‘shadow factories’), plants fully equipped for production at the outbreak of hostilities. This was an economy entirely centred upon non-reproductive values and, except for exports, upon non-marketable goods.

These non-reproductive values were paid for by the State by means of special bills which could be used for paying subcontractors, but which could on no account be cashed in money expendable in the market for consumer goods and thereby inevitably causing inflation. For in the civilian sector, as we may call the sphere of reproductive values, all wages and prices were pegged under decrees of ‘wage stops’ and ‘price stops’ to be upheld by the whole power of the Nazi terror machine. Hence the entirety of the civilian sector was planned by the Nazi powers to retain a fixed magnitude throughout the years of war preparation. However, even the strictures of the Nazi terror could not fully ensure the plan. The quantities of the civilian goods and their means of production could be controlled. But the qualities could not be maintained owing to the lack of raw materials and their replacement by substitutes. This caused deteriorations and price rises and set in motion an increasing measure of inflation. However, these were details that acted as flaws to the system but could not make the fascist economy entirely unworkable.

A Marxist analysis will help us to understand the system more fully. We know that capitalist profits are reaped from the amount of work which labourers perform over and above that necessary to produce the value of their wages. This unpaid labour represents the ‘surplus value’ which can be ‘absolute’ or ‘relative’. It is called relative when its extraction is associated with increased labour productivity because it can be enlarged without an extension of the labour time. This implies a general technological advance of society and marks a progressive stage of the capitalist mode of production. In the early epochs of capitalism the measure of the surplus value simply depended on the absolute length of the working day and, when this met with outer limits, it depended on the speeding of labour. This Marx calls ‘absolute surplus value’ because the technical and the social conditions of labour then are tantamount to a fixed, absolute magnitude. Judged from the angle of these Marxian categories the essence of the fascist economic system is recognisable as a reversion of the capitalist mode of production from the relative to the absolute surplus value extraction. The rate of accumulation is raised by depressing the rate of consumption, and the surplus product cannot be of a consumable and marketable kind.

In the ‘Sozialistische Warte’ (Socialist Guard) of June 15, 1937 (year 12, No. 12) Fritz Kempf calculates on the basis of the official German statistics that in 1936 the German working-class including white-collar workers and civil servants had as a whole to make do with the same total income as in the slump year 1932, although the number of employed had risen from a mere 12.5 million in 1932 to 17 million in 1936. The number of hours worked in industry had gone up by 84%. Admittedly, nominal wages and salaries reached 35 billion reichsmarks compared with 26 billion in 1932. But if account is taken in the latter case of all the increments and bonuses such as unemployment benefit, health and social insurance grants, rent rebates, winter-aid, butter subsidy etc. and for 1936 deduction is made of all the compulsory taxes, social services and obligatory charity contributions, total consumable income comes to 29.4 billion reichsmarks before 1933 and to 34.5 billion for 1936. Thus there was a nominal increase of 19% which Kempf rightly regards as easily cancelled out by rising prices and quality deterioration of consumer goods. And this makes no mention of the vastly increased tempo of labour in the workshops ‘compensated’ by an effective nil-rise of wages since 1933.

Total investments over the ten years between 1928 and 1937 were as follows (in billions of Reichsmark):

1928: 13.8

1932: 3.9

1933: 5.1

1934: 8.3

1935: 11.2

1936: 13.5

1937: 15.5

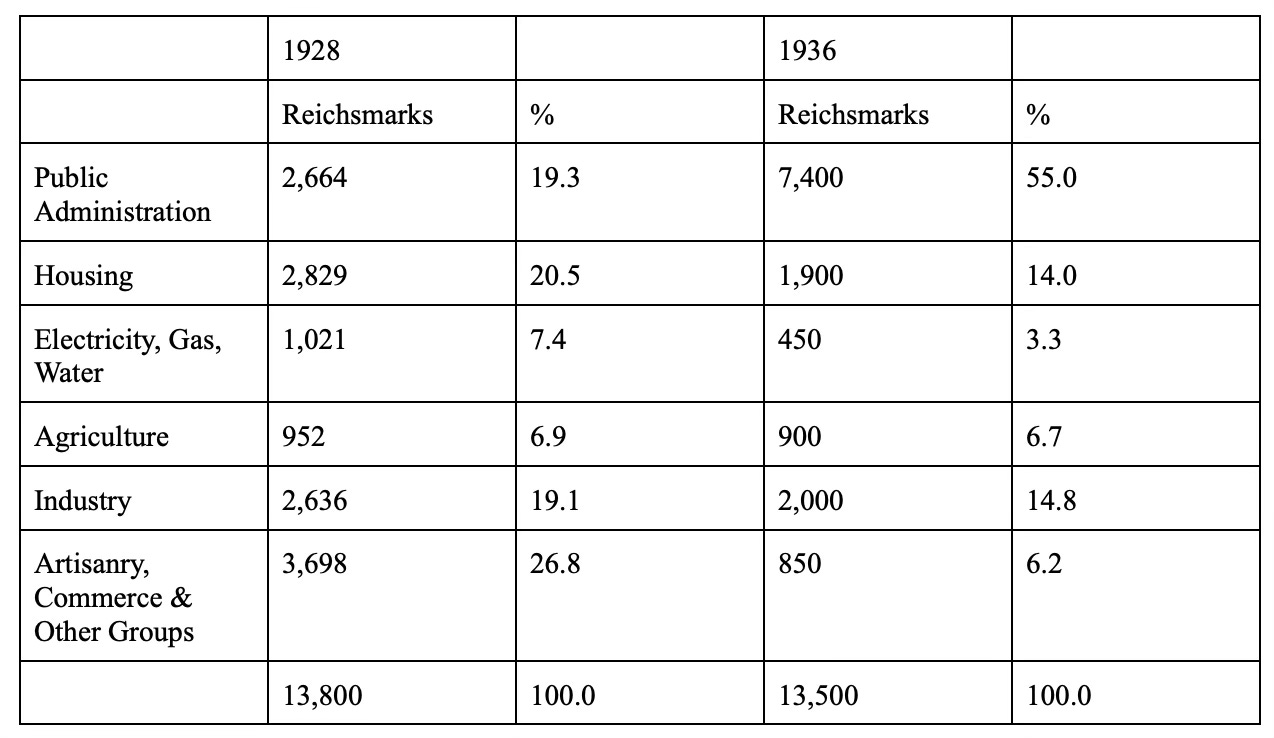

The inner distribution of these investments over the various sections of the economy reveals the significant differences of 1936 as against 1928 (in millions of Reichsmark):

For 1936 we have to take into account that according to the official Reich statistics, public investments also spread into ‘industry’, ‘agriculture’ and ‘other groups' so that for 1934, for instance, the investments emanating from the State made up 70% of the total. Some of these public investments had borne private benefits which continued reaping private fruits and within the Second Four Year Plan were intended to do so. As a result of this development the production index of the consumer goods industries lies in 1937 4.6% above that of 1933, whereas the index for the investment goods industries, almost totally absorbed in armaments, exceeds that of 1928 by 33%. Since 1933 the output of the investment goods industries had almost trebled, while the production of consumer goods industries grew by just one third counted in money value, which lost about that much in its purchasing capacity. Remarkable also is the fact that a reduction to less than one quarter occurred in the investments for ‘artisanry, commerce and other groups’, covering sectors of the economy where the Nazis had originally found their most numerous and most ardent followers. In 1938 the Hitler Government decreed the most detrimental legislation to the small traders ever published in Germany, which goes to confirm that the fascists in power are not the same as the fascists fighting for power.

In 1937, the system of absolute surplus value was threatened by the beginning of serious shortages of labour, especially in metal working and the building trade. It became more and more frequent for employers to lure each others’ workers away by offering higher pay, and more and more the workers themselves stood up for better working conditions as well. In a document of March 1937 issued by the Ministry of Economics we read a reasoning for refusal of payment for occasional holidays: ‘increase of wages without increased labour is in contradiction to the policy of the Government. There is no money available for wage increases which inevitably involve price rises causing an unending spiral on the home market and loss of competitiveness abroad.’1 Obviously, the one thing never considered was increased production of articles for workers’ consumption.

The labour shortage went from bad to worse, until in 1938 it reached such dimensions that the Government imposed a compulsory Labour Service as the only means of preventing the disruption of the entire fascist economy. The workers recruited into the Service derived no wage claims from it. They were counted as on leave from their last employment, and that ‘leave’ was paid by their previous employers, not in full however, since the recruits were offered free accomodation and food. In this way the compulsory Labour Service made sure of not running into ‘contradiction to the policy of the Government’ in matters of workers’ pay. The number thus recruited up to the outbreak of war was 800,000, half of them used on the building of the Westwall, the Siegfried Line, the counterpart to the French Maginot Line.

The employers from whom the recruits were drafted did not, of course, happily part with men whom they needed no less essentially than did the Westwall. Which employer was hit and to what extent depended on his local Nazi authority (called the ‘Gauleiter’) and almost certainly the choice fell not upon the military but upon the civilian manufacturers, those producing reproductive values. ‘Guns before butter!’ was Göring’s slogan.

The compulsory Labour Service illustrates that whenever the Nazi system of absolute surplus value ran into straights, it was the paid part of the labour, the wages, that was nipped, and that if the necessity for its payment could be no further curtailed, the public robbers of the unpaid labour robbed the private robbers.2 The fascist system of economy was not all paradise for the employers either, not even for those creating the non-reproductive values to which attached all the prerogatives. What advantage did they derive from the bills that accumulated in their ledgers, padded though they were with extra generous profit margins? They were values only on the assumption that the war to come would be won by Germany, or that the victims could be blackmailed into bloodless surrender. We have mentioned how these German arms producers were sometimes gripped by panic at facing what Goerdeler in 1935 had called ‘The true state of affairs in Germany’ and how they were then brought to the edge of pseudo-revolt. Right from the beginning, the Hitler-regime and its fascist economy were not the free choice of the capitalists, who were caught in the dialectic of contradictions that they could not avoid.

When the war preparations in 1938 ran short of raw materials and of industrial plant as well as of labour, the robbing had to start even before the outbreak of the major war by the annexation of Austria and of Czechoslovakia. Here for the first time the promissory profits could be given real substance without extra pay other than the military cost of the robbery. In 1940 the cost of defeating France and forcing the greater part of French industry into a fifty-fifty deal with the German industrialists was more expensive but the gain immensely greater since the booty included the riches of Holland, Belgium, Luxembourg, Denmark and Norway. If at that point Hitler had been contented with the gains achieved, the fascist venture could have paid Germany with glamour, glory and substance. But as we all know, Hitler had ascended to his place in history in order to save the European Culture from Bolshevism and it was by attempting this feat that the fascist barbarism missed its triumph.

Timothy W. Mason, Arbeiterklasse und Volksgemeinschaft, Westdeutscher Verlag. 1975

Keep in mind that the entire crisis of the German economy from the end of World War 1 was brought on by an over accumulation of capital, constant capital according to Sohn-Rethel. Curtailing wages, the variable part of capital, does nothing to resolve the problems stemming from this over accumulation, but, on the contrary, intensifies them. Once again, even as the German economy appeared to be rebounding to an extent in the 1930s, we can see it simultaneously sinking deeper into the contradictions which were driving it towards another continental war. Theoretically, such a crisis might be resolved by an increase in the variable part of capital, but this was not possible in Germany, and so the Nazi government lurched from one contradiction to another, putting out one fire at a time by drowning each one in gasoline. — Bluebird